Unraveling the Secrets of the Salter: Tracking Brook Trout on the Quashnet River

Using a syringe to inject a passive integrated transponder (PIT) tag into the abdomen of a Brook Trout.

Winding through Cape Cod’s Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge, the lower Quashnet River flows with more than just water—it carries the living story of one of New England’s most remarkable ecological recoveries. Once straightened and degraded by cranberry farming, this spring-fed stream has spent the last fifty years healing, thanks to a coalition of restoration scientists, conservation advocates, and grassroots volunteers. Today, its cold, oxygen-rich waters are once again home to wild Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), including a rare and resilient form known as the "salter"—a trout that ventures beyond its freshwater birthplace to forage in the brackish tides of nearby Waquoit Bay.

To understand how these fish are responding to their revitalized home, researchers have turned to cutting-edge technology: Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tagging. This technique, akin to an EZ-Pass system for fish, is helping scientists decode the complex behaviors, migrations, and habitat needs of a species that had all but vanished from much of the region.

A passive integrated transponder (PIT) tag, barely larger than a grain of rice, is placed in the abdomen of a fish. The tags use radio frequency technology to communicate with antennas placed within the river.

A High-Tech Window into a Hidden World

PIT tagging involves implanting a tiny microchip—no bigger than a grain of rice—into the abdominal cavity of a trout. Each chip carries a unique ID, which can be detected by antenna arrays placed at key locations along the river. Every time a tagged fish swims past an antenna, the system logs the moment, silently recording its journey.

Unlike traditional tracking methods, PIT tagging is non-invasive and requires no recapture. Solar-powered systems gather thousands of detections per year, creating an unprecedented dataset on fish movement, behavior, and survival. Since 2005, the lower reaches of the Quashnet have been outfitted with this technology, transforming the stream into a living laboratory for ecological research.

The results have been revelatory.

A passive integrated transponder (PIT) antenna array deployed on the Quashnet River. The solar panel provides power for the antenna and the computer which records the data (stored in weather-tight box behind the solar panels).

Tracking Trout, Telling Stories

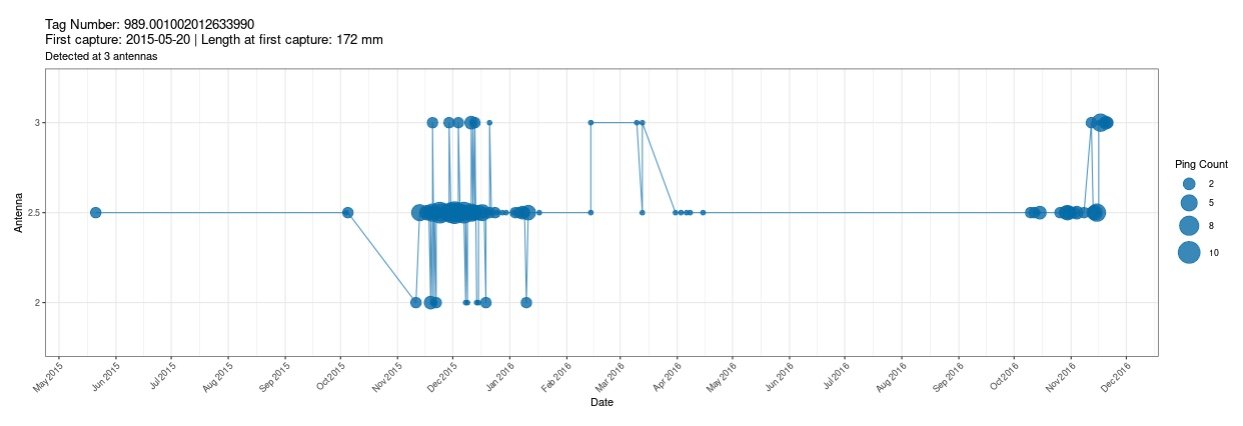

Behind every data point lies a living fish with its own unique story—individual journeys that reveal just how dynamic and adaptable Brook Trout can be. Take, for example, one fish tagged in early May 2015, measuring 172 mm at the time. For much of the year, it remained in the upper reaches of the Quashnet River, a behavior typical of trout seeking cooler, spring-fed waters. But in a surprising twist, this fish ventured into the tidal lower river during the fall—precisely when many Brook Trout are expected to be upstream, focused on spawning. This unexpected movement challenges long-held assumptions about seasonal behavior and underscores the ecological complexity of partially migratory populations. Thanks to the power of PIT tagging, these kinds of fine-scale movements—once invisible to researchers—are now captured in rich detail. They offer an unprecedented window into how individual fish respond to subtle shifts in flow, temperature, and habitat, and how they navigate a restored system that offers both freshwater sanctuary and estuarine opportunity. Each story deepens our understanding of the species and helps guide future conservation strategies.

Movement of a tagged Brook Trout over time as it was detected by passive integrated transponder (PIT) antennas along the Quashnet River. The fish was first captured in the middle reach of the lower Quashnet during spring 2015, and later traveled upstream and downstream as recorded by the antenna detections.

Fish behavior on the Quashnet has been anything but uniform. Some trout roam far and wide; others hardly stray from the spot where they were tagged. These differences aren't just interesting footnotes—they're central to understanding how trout populations navigate habitat changes, competition, and climate stress. PIT detections show that some fish are venturing into estuarine waters and returning, sometimes making the journey several times a year. Others seem to shift their tactics with the seasons. This kind of behavioral flexibility is a good sign: the trout aren’t just hanging on—they're adjusting, finding new ways to thrive. Their comeback is a reminder of how important it is to protect both freshwater streams and coastal estuaries. Salters, in particular, depend on unbroken pathways between river and sea to complete their life cycles. Yet not every Quashnet River trout takes to the tides—and so the story of the salter remains as complex and fascinating as ever.

Steve Hurley, retired MassWildlife biologist, measures the length of a Brook Trout before taking a weight measurement.

Measuring Resilience in Fish and River

To fully assess the health of the Quashnet River's Brook Trout population, scientists go beyond simply counting fish and watching where they travel. They examine key biological metrics that offer a deeper look into how these fish are growing, surviving, and thriving in their restored habitat.

Length-weight relationships are one such tool. By looking at how heavy a fish is relative to its length, researchers can estimate individual condition—whether a trout is lean or plump, growing quickly or slowly. A high condition factor typically suggests good feeding opportunities, while low values may indicate stress, competition, or poor resource availability. On the Quashnet, these values have remained relatively stable over time, suggesting that food resources have not significantly changed—a good sign in a dynamic, recovering system.

Length frequency distributions add another layer to the picture. By capturing the spread of fish sizes across time, these data reveal the presence of multiple size and age classes—from young-of-year to older adults. This size structure is often lacking in degraded or overfished systems. Its presence in the Quashnet speaks to strong reproduction and successful recruitment—clear indicators of ecological recovery and habitat suitability.

Length frequency distribution of Brook Trout captured during the spring and fall electrofishing surveys on the Quashnet River in 2024.

In the Quashnet River, fishing is catch-and-release, so very few fish die as a result of being caught (though it’s probably not zero). That makes it a great place to study natural mortality—the number of fish that die each year from things like predators, disease, or simply getting old. To estimate this, we use a method called a catch curve, which looks at how many fish of each age are caught in surveys. From that, we calculate something called the instantaneous rate of natural mortality. It sounds technical, but it just describes how quickly fish are dying over time. For the Quashnet, that rate is around 1.2. On its own, that number might not mean much—but when we convert it into something easier to understand, it tells us that only about 30% of the fish survive from one year to the next. In other words, roughly 70% die each year from natural causes.

That may sound like a lot, but it’s actually quite normal for wild trout populations, especially in dynamic stream environments like this one. In systems with high natural mortality, we also expect the fish not to live very long. In this case, a rate like this suggests a maximum age of around 3.6 years, which matches what we’ve seen in the data. Understanding this rate helps us get a clearer picture of the population’s health and life cycle—important information for managing and restoring wild trout streams like the Quashnet.

This high mortality rate highlights the importance of strong annual reproduction to sustain a healthy population. Given the substantial losses due to natural causes, successful recruitment (the addition of new fish each year) is essential for maintaining population stability. This insight is critical for informing management decisions, ensuring that fishing pressure does not interfere with the natural recovery and sustainability of the population.

Growth rates offer yet another window into trout life histories. On average, Quashnet Brook Trout grow about 3–6 cm (1.2–2.4 inches) per year, with faster growth observed in younger fish. These growth patterns are influenced by temperature, food availability, competition, and habitat complexity—factors that vary throughout the stream network and from year-to-year.

Brook Trout length-at-age data from the Quashnet River, with a von Bertalanffy growth curve fitted to describe growth patterns.

But these successes are not uniform. The biological patterns captured through these data highlight a striking diversity of life strategies at play. Some trout grow rapidly, taking advantage of warmer, food-rich reaches. Others appear to trade off fast growth for better survival in colder, more oxygen-rich headwaters. This variation reflects the flexibility and adaptability of the species—and points to the importance of maintaining a mosaic of habitats within the system.

Understanding this diversity is essential for long-term management, especially in the face of climate change, which threatens to disrupt stream temperatures, flow regimes, and food web dynamics. By tracking these biological metrics over time, managers can better anticipate changes, identify emerging stressors, and ensure that the Quashnet continues to support a resilient and self-sustaining Brook Trout population.

From Field to Screen: A New Way to Explore

To make the science accessible to all, the Waquoit Bay Fish Company has developed the Quashnet River Brook Trout Data Viewer—an interactive dashboard that brings the lives of these fish into focus. This dynamic tool allows users to track individual fish movements, explore seasonal activity patterns, and dive into biological metrics like size distributions, condition factors, and growth curves.

Screen shot from the new Quashnet River Brook Trout Data Viewer application available at: https://mcpalmer.shinyapps.io/Quashnet_River_Brook_Trout/

The app also features mapped antenna locations and tagging sites, offering a clear visual of how Brook Trout navigate and interact with their restored habitat. Whether you're a student, angler, biologist, or just curious about river life, the viewer provides an engaging window into the daily rhythms of a recovering wild trout population.

It’s a powerful example of citizen science in action—transparent, data-rich, and designed to foster connection between people and the ecosystems in their backyard.

Restoration, Rooted in Collaboration

The revival of the Quashnet didn’t happen by chance. It’s the result of a decades-long collaboration between state agencies, scientists, local volunteers, and community advocates. Among the most influential figures were Steve Hurley, a visionary fisheries biologist with MassWildlife, and Fran Smith of Cape Cod Trout Unlimited. Hurley has championed the return of Brook Trout to southeastern Massachusetts coastal streams, while Smith galvanized local support, labor, and funding to protect and steward the river.

Their combined efforts transformed a straightened agricultural ditch into a dynamic, meandering river system teeming with life. Today, the Quashnet stands as one of the best examples of coldwater restoration in Massachusetts—a case study in how science and community can work hand-in-hand to heal an ecosystem.

Fran Smith (left) and Steve Hurley (right) share a story before a recent Brook Trout survey.

A Blueprint for the Future

The story of the Quashnet River is ultimately a story of resilience—of a landscape healing from its industrial past, of a native fish reclaiming lost territory, and of a community committed to restoration. PIT tagging has not only provided the scientific foundation for understanding that recovery, but it’s also sparked a broader conversation about how we track, protect, and coexist with the natural world.

As climate change, development, and ecological disruption continue to reshape our rivers, the lessons from the Quashnet are more relevant than ever. With continued monitoring, community engagement, and habitat protection, this once-forgotten stream has become a symbol of what’s possible—not just for Brook Trout, but for ecosystems across the continent.

Today, the story of the Quashnet continues to evolve. Current efforts are focused on expanding restoration work into the upper reaches of the river, where decades of channelization and cranberry agriculture still limit habitat potential. This next phase aims to re-naturalize the upper river channel, remove remaining barriers, and reconnect vital spring-fed tributaries. By restoring flow, complexity, and access to cooler headwaters, the project will open up critical new refuge for Brook Trout. Learn more at apcc.org/upper-quashnet-river.

A restored section of the lower Quashnet River, featuring added woody debris and rocks to enhance the stream channel. These habitat improvements were carried out by dedicated volunteers from Cape Cod Trout Unlimited, working to support and restore Brook Trout populations.