Bankers’ Hours to Bankruptcy: the Collapse of Gulf of Maine Cod

The author holding an approximate 40 lb cod caught in the western Gulf of Maine.

In the late-2000s I could still talk myself into believing in a happy ending for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in the Gulf of Maine.

By my early thirties, a few years out of grad school, I’d landed at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. There, I started trading seminar rooms for wheelhouses and survey decks. Growing up in Massachusetts, I’d been marinated in stories of New England’s fishing past and had already chewed through a small library of books on the region’s fisheries—the mythical pull of cod, its role in building coastal towns, its almost ceremonial standing in the Commonwealth. Cod wasn’t just a data point to me; it was the fish that paid for wharves and steeples, the fish that earned a wooden effigy in the State House chambers. This was the state that cod built.

From the docks in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, the story still sounded almost cheerful. Boats were sailing at reasonable hours, towing close to home, coming back with what, on the surface, looked like solid trips. The joke among Gloucester fishermen was that cod fishing had turned into “bankers’ hours”: no more brutal all-nighters chasing scattered fish over the horizon. Cod seemed thick near the western Gulf of Maine ports, and for a little while the mood—if not jubilant—was at least cautiously hopeful.

On paper, the numbers backed that feeling up.

In 2008, a federal stock assessment—a kind of fisheries “report card” that uses surveys, catch data, and computer models to estimate how many fish are out there and how much can be sustainably caught—concluded that Gulf of Maine cod had rebuilt to about 58 percent of its target spawning biomass, with projections that the stock might be fully rebuilt by 2010. After decades of decline and increasingly strict regulations, it was the storyline everyone wanted: sacrifice, recovery, vindication.

Out at sea, though, standing on the wet deck of an aging NOAA survey vessel, I was watching a different reality play out with each haul-back.

That fall I was aboard the Albatross IV, the old workhorse of the Northeast groundfish survey, steaming from station to station across the Gulf of Maine. The rhythms of that work are still in my muscles: lower the gear, tow, haul back, swing the codend aboard, open the net, dump the catch and sort—flounders, redfish, skates, haddock, a few cod. Measure, weigh, record. Reset. Repeat.

What I remember most clearly from those trips is what I didn’t see.

For a stock supposedly halfway rebuilt, there were strikingly few cod coming up in the net. Basket after basket of mixed groundfish, but the big, iconic cod that had built New England’s fishing ports were conspicuously scarce. It felt less like recovery and more like a rumor we were all trying to believe.

The models back on land said cod were recovering. Catch rates close to port seemed to say something similar. But the surveys I was working were whispering another story—quieter, more troubling, and much harder to forget once you’d seen it. What stayed with me wasn’t the sight of cod; it was how often they simply weren’t there.

At the time, I kept trying to believe there was some neat way to reconcile those contradictions. I just didn’t yet understand that, for the next decade, I’d be standing squarely in the middle of them.

A New England ground fisherman working up their catch from a bottom trawl.

Stepping into the wheelhouse

For a couple of weeks each year, I went to sea on the federal surveys, watching fish come up in real time—seeing what was actually on the bottom, not what a model thought should be there. The rest of the year, I lived in two overlapping versions of the fishery: the one in wheelhouses and logbooks, and the one on my laptop and in meeting rooms far from the water.

Part of my work was shoulder-to-shoulder with fishermen. I rode along on commercial vessels, working with skippers to build electronic logbooks that captured their trips tow by tow. Back on land, I set those self-reported records against data from at-sea observers and vessel tracking systems, testing how well they held up so we could use fishermen’s information directly in the science. We were trying to turn wheelhouse knowledge into something that counted in the models—and, just as importantly, into trust.

The other part of the job—assessing fish stocks—lived in the engine room of the science. I spent long stretches buried in computer code, tuning assumptions and coaxing models into converging, then carried the output into rooms under fluorescent lights, explaining PowerPoint plots to tired fishermen, impatient advocates, and council members trying to reconcile biology with someone’s mortgage payment.

I’d been on the groundfish assessment team for a few years when my supervisor—the person who’d carried the Gulf of Maine cod assessment for as long as I’d known—retired. When the question of who would take over came up, I raised my hand, not fully grasping what it meant to step into the driver’s seat of the region’s most iconic stock. That’s how I ended up as lead stock assessment scientist—a nearly decade-long run that felt like grabbing the wheel just as the entire dashboard lit up with warning lights.

Living inside the assessment meant living inside the numbers: landings and discards, survey indices, age and length compositions. The deeper I went, the more I saw how much wishful thinking had been mortared into the stories we told about recovery.

Those stories began to unravel in 2011.

Hauling in the net on the NOAA fisheries research vessel Albatross IV.

When the floor dropped

The 2011 benchmark assessment for Gulf of Maine cod—my first as lead—was supposed to be a careful reset, not a bombshell. Benchmark assessments are when you’re allowed to bring in new tools: updated ways of handling the data, revised assumptions, and, in this case, a new model. The expectation going in was modest. We might sharpen the picture, maybe nudge the trajectory a bit. Nobody thought we were about to turn the story upside down.

Most of what we changed would have sounded like housekeeping to anyone outside the room. We fixed how we converted between estimated fish numbers and weights—reshaping our picture of how much cod biomass we thought was out there. We stopped pretending every survey number was equally solid; some estimates were clearly noisier than others, so the model let them tug less on the final answer. And we gave the model a bit more room in how it followed the catch history. On paper, it was just a different way of reading the same history—in practice, it was better science.

But once the new model was fully wired up and the data were pushed through, the stock we thought was more than halfway rebuilt suddenly shrank. Cohorts we’d been counting on all but vanished, and historical biomass estimates fell by more than 70 percent. The recovery narrative that had been built over the previous decade—sacrifice, rebound, vindication—collapsed in a few pages of output.

My lane in all of this was narrow but well defined: assemble and vet the data, choose and run the models, and explain what the results did and didn’t mean. I didn’t vote on quotas; I handed managers the best picture we could produce, uncertainty and all, and they decided what to do with it.

The people holding the levers of management didn’t like what they saw. Neither did much of the industry. The assessment was criticized from every angle—data inputs, model choice and structure, reference points. Under that pressure, the big cuts implied by the 2011 results were softened and delayed, and instead of fully acting on them, the system asked for a do-over.

Years earlier, Congress had written the law that said we would base catch limits on science and rebuild depleted stocks. We were just doing the work the statute required. But when the results pointed toward painful cuts, some of the same elected officials who’d helped pass that framework into law turned around and attacked the science and the policies that flowed from it.

As Senator John Kerry wrote to the Secretary of Commerce on December 14, 2011: “This GOM cod situation is further proof that the entire research and data process needs to be completely overhauled. Therefore, in conjunction with the new assessment for GOM cod, I ask that you undertake an end to end review of the stock assessment process that includes the analysis and recommendations of outside parties.”

So in 2012 we did the whole thing again. We re-opened the hood, ran alternative configurations, invited more reviewers, and stress-tested the conclusions in every direction. I even managed to get married in the middle of it—no honeymoon, just straight back to cod and council briefs. When the rerun was over, the answer remained the same: Gulf of Maine cod were in far worse shape than we had once thought.

While we argued about the assessment, we continued to overfish.

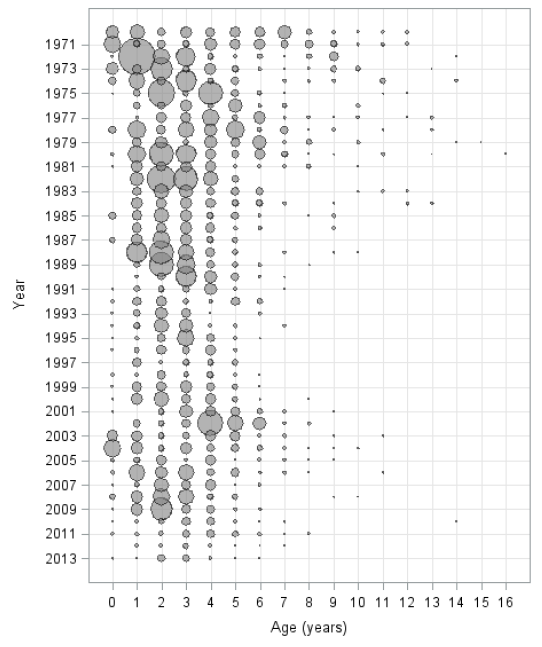

Bubble plot showing fall survey estimates of cod abundance by age from 1963 to 2013. Each bubble marks a year–age combination, with larger bubbles indicating more fish. Note the absence of old fish in recent years. Source: NOAA

The secret assessment

In the years after the 2012 rerun, the surveys never really gave us a way out. Season after season, the plots came back with the same hollow outline: weak year classes, low indices, too few small fish stacking up behind the older ones. We kept waiting for a pulse of recruitment that would show up first as a wave of small cod in the gear and then march up through the age classes over time. It never did. The information we were seeing just kept getting worse.

In the summer of 2014, I ended up running an off-schedule update of the model in a strange stretch when my wife was late in her pregnancy with our first child. I wasn’t hunting for extra drama. The stock was already slated for a full assessment in 2015, and on paper, we could have waited for the scheduled check-up. But those interim survey numbers kept landing on my desk with the same message: still low indices, still no sign of the wave of young fish we were counting on. After a while, it was hard to keep telling myself that time alone might fix it. Curiosity and worry finally tipped the balance. I took the same peer-reviewed model we’d used in 2012 and quietly pushed the data window forward. A couple of close colleagues helped me check the data, the code, the outputs. The question was simple: if we trust our tools, what do they say now?

The answer was blunt. The new runs put the stock at a sliver of its rebuilding target and showed we were still fishing too hard, even after years of cuts. This wasn’t a result you could hide in a drawer and move on from. Staying quiet would have been unconscionable. I brought the results to my supervisors and laid it out as simply as I could—this is where the model puts us with the current data.

Not long after that, the numbers slipped out of the narrow circle they’d been living in. As soon as word of the off-cycle update and its conclusions reached beyond the inside channels, the reaction was immediate and loud—calls, emails, side-door conversations, council members wanting to know who had authorized what. The usual advisors leaned into the same line of attack, drilling into who had requested the work, whether it fit neatly into the existing schedule, and which procedural boxes had been checked, rather than grappling with what the numbers themselves were saying about the stock. Before the hastily arranged peer review could even convene, parts of the fleet were already calling it the “secret cod assessment,” as if it had been stitched together in a back room to change the rules overnight.

From where we sat, there was nothing secret about it. It was a small group of scientists asking a straightforward question—what do the models say now?—and being honest about the answer. In many ways, that early, uncomfortable update helped stall an ecological tragedy already in motion. There were no celebrations for that—only scrutiny and criticism—but sounding the alarm was the job.

By the time those runs had been turned into formal documents, peer-review reports, and council briefing decks, my wife was home with a newborn and I was spending long days in meeting rooms trying to explain what we’d found. The warning we’d been sounding since 2011 hadn’t gone away. It had simply come into sharper focus, faster than the machinery of process could catch up.

Sorting the survey catch in the middle of the Gulf of Maine.

Bankers’ hours, sand lance, and hyperstability

From the perspective of broad-scale surveys, the picture was dark.

For years, some in the industry argued that the surveys were simply missing cod. Their skepticism was understandable. If you can still fill your hold in your best spots but the survey index is falling, it’s tempting—almost irresistible—to believe the survey must be wrong.

And there were, to be fair, plenty of technical questions to point to. The survey trawls weren’t the same as commercial gear. Their doors spread differently; their nets fished a little higher or lower; their tows were shorter, slower, more standardized. When NOAA transitioned from the old Albatross IV to the newer Henry B. Bigelow, we spent years talking about “calibration,” “catchability,” and how to make the numbers line up. Were we catching a smaller or larger fraction of the cod than we used to? Were we fishing over the wrong bottom types at the wrong times? Were we simply towing past them?

Standardized trawl surveys are designed to sample a wide variety of depths and bottom types in a consistent way over time. They show you the whole stock area, not just the hot spot of the month. But they don’t fish safely over the steepest, rockiest edges, and they will never behave exactly like a working dragger. When cod retreat into rougher nearby ground, survey catch rates can plummet even while catch rates in a few favored fishing spots stay high.

Those were real, worthwhile scientific questions. The problem was how they were used.

A small but influential set of voices in the management process—industry representatives, academic consultants, and a few advisors—leaned hard on those uncertainties. They highlighted every potential bias that might make the surveys look too pessimistic and treated them as proof that the stock was healthier than the assessments suggested. Questions about gear efficiency, selectivity, calibration coefficients, and survey design became a kind of fog. Whether intentionally or not, the effect was to keep attention focused on what might be wrong with the warning lights, rather than on the very real possibility that the engine itself was failing.

I worried about that too. In my world, those worries turned into more work—more analyses, more diagnostics, more time digging through the data for anything we might have overlooked.

Those concerns also drove NOAA and its partners to build new surveys aimed directly at the places the fleet fished and at the kind of bottom our standard trawls didn’t cover—rocky ground, bank edges, the haunts where big cod might be holed up. If there were pockets of cod the NOAA surveys were missing, those targeted surveys were our best chance to find them.

They didn’t.

The surveys caught cod, but not in numbers that could rescue the assessment. Across methods and habitats—on mud, sand, and rock, inside and outside hot spots—large, old cod were rare. The fish we did see were often middle-sized, with comparatively few large, old cod in the mix. That’s not what you expect in a healthy stock. In a population that’s doing well, you see a full range of sizes and ages: lots of small fish coming in, plenty in the middle, and a healthy share of older, larger cod that have made it through multiple spawning seasons. What we were seeing instead was a truncated population—too few old fish surviving through, a sign that overall death rates were still high.

What eventually became clear was how sand lance—a favorite prey of cod—had helped create the illusion. As sand lance abundance boomed and they packed in along a small slice of Stellwagen Bank, cod stacked up on that same patch of bottom, and the fishery piled in after them. Nearly half of all Gulf of Maine cod landings were suddenly coming from a tiny fraction of the stock area, and both catch rates and survey indices in that one neighborhood stayed high even as the overall stock declined—a textbook case of hyperstability built on the back of a little forage fish.

By the time this became undeniable, we had already spent years letting high localized catch rates, shifting prey fields, and a constant chorus of “what if the surveys are wrong?” create the illusion of abundance. We let the comfort of “bankers’ hours” on sand-lance-fed cod, and the politics of uncertainty, override the warning lights on the dashboard.

In the end, it is a fish story of epic proportions—but not the triumphant kind. It’s the story of how a management system built on days-at-sea, a boom in tiny forage fish, and a persistent focus on doubt helped a hand-sized sand lance hide the collapse of this iconic fish.

This figure shows spring survey catches of Gulf of Maine cod from 1968 to 2016. Over time, cod mostly disappeared from much of the Gulf, even as catch rates stayed high in the western Gulf of Maine. The big spikes in 2007 and 2008 come from just a few very large tows on Stellwagen Bank, which made the survey numbers for those years look high, but also very uncertain.

Models that rewrote their own history

While the public arguments swirled around survey gear, calibration coefficients, and whether the trawl was “missing fish,” a quieter alarm was going off in the background—inside the cod stock assessment model itself.

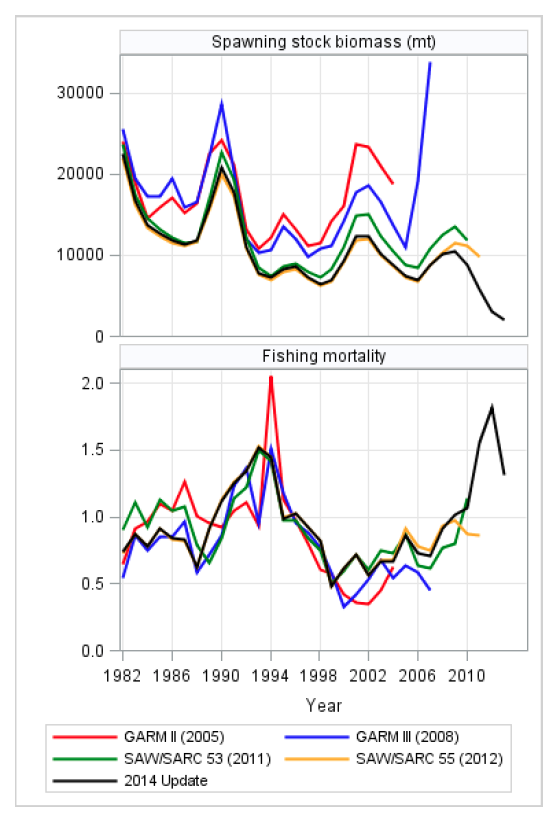

Gulf of Maine cod had what we politely called a “retrospective pattern.” In practice, it meant that every time we updated the assessment, the model rewrote recent history. Years we’d just finished calling “okay” were, in the next assessment, quietly downgraded: the same past biomass estimates slipped lower, and the same fishing mortality estimates crept higher. With each new run, the recent past looked a little worse than we’d believed it to be at the time.

By the time I was leading the assessment, that pattern wasn’t just a technical nuisance; it signaled that earlier assessments had been systematically too optimistic. The cod story we’d been telling ourselves for the previous decade was being rewritten, and every new draft pushed the plot in the same direction.

There was no single smoking gun, just several plausible suspects behind the retrospective pattern.

Catch estimates—especially discards—were almost certainly too low. Natural mortality may have increased as the Gulf of Maine warmed and ecological relationships shifted; rising gray seal numbers may have been part of that story, though their exact impact on cod remains uncertain. Yet most of our models held natural mortality fixed, as if the background risk of death for cod never changed. And evidence was piling up that “Gulf of Maine cod” was less a single, uniform stock than a patchwork of partially distinct spawning components, each with its own productivity and vulnerabilities. Lumping them together blurred important dynamics and made declines in weaker components easier to miss.

Individually, none of those ideas was especially radical. Taken together, they carried a brutal implication: rebuilding plans based on earlier, rosier assessments had asked too much of the stock and allowed too much fishing for too long.

You didn’t need a grand mystery to explain what happened next. You needed to look at how, when faced with uncertainty, we kept making choices that leaned toward higher catches and delayed pain.

That conclusion did not land gently in the rooms where quotas were set.

Comparison of estimates of spawning stock biomass and fishing mortality from stock assessments completed in 2005, 2008, 2011, 2012, and 2014 showing the over-estimation of stock size and under-estimation of fishing mortality in prior assessments. Source: NOAA

Science for hire and the erosion of caution

As the science became more alarming, the politics surrounding it grew sharper.

When official assessments warned that cod were in deep trouble, segments of the industry increasingly responded by commissioning their own analyses. Outside consultants—often respected quantitative academic scientists—were hired to critique government models, reanalyze data, or generate alternative population estimates.

Sometimes those critiques caught real problems. No assessment is perfect; outside eyes can be invaluable. But over time, a pattern emerged that was hard to ignore: industry-funded science almost always bent in one direction. It emphasized uncertainties and alternate interpretations that could justify higher catches or delay cuts, rarely the reverse.

In public debates, phrases like “science for hire” started to surface. In council meetings, dueling narratives about stock status became weapons rather than tools.

That erosion of precaution wasn’t abstract. You could see it in the model choices. Industry consultants often pressed for strongly domed selectivity in the assessment models—telling the model that mid-sized cod were easy to catch while the biggest, oldest fish mostly slipped through. On paper, it turned the absence of large fish into “cryptic biomass” lurking just out of view. To be fair, later work has shown that regulations and fish movements can make fishery selectivity dome-shaped, but there was little evidence that either the surveys or the fleet were missing a large, hidden reserve of old cod.

You could see it again in the population projections built off those consultant runs. The rebuilding deadline stayed the same on paper, but the bar for what counted as “rebuilt” moved. By swapping in different recruitment assumptions that said cod could hit peak production of young fish at a smaller stock size, it made it easier to claim we were on track without actually putting more cod in the water.

From my seat at the science table, I watched the uncertainties I saw as reasons for caution repurposed as excuses for inaction. If surveys might be missing cod, if models might be biased low, if a consultant could spin up an alternative set of numbers with a higher biomass line—there was always an argument for waiting one more year before making the really hard cuts.

It also took a personal toll.

I didn’t go into this line of work to end up as part of anyone’s script. I went because I believed that if we told the truth about the numbers, we could chart a path that kept both cod and coastal communities alive. Watching that truth repeatedly softened, sliced, or postponed was its own kind of grind—one that doesn’t appear in any appendix.

Climate as backdrop—and as alibi

Even if management had been flawless, cod were sailing into a stiff headwind: a rapidly warming Gulf of Maine.

Over just a few decades, the Gulf of Maine warmed faster than almost anywhere else in the global ocean. For a cold-water species like cod, that is not a parenthetical detail. Warmer water erodes egg and larval survival, pushes prey into new neighborhoods, scrambles spawning timing, and ratchets up metabolic stress. Bit by bit, warming eats away at a stock’s ability to replace itself.

By the time I was deep in the assessment work, several studies were already warning that our rebuilding plans rested on an ocean that no longer existed. The catch limits that had once looked cautious against the backdrop of a cooler, more productive Gulf of Maine were, in the new climate reality, quietly too high. On paper, the plans still spoke the language of recovery. In the water, the conditions underpinning that recovery were slipping away.

We could see the depth of the problem most clearly in recruitment—the flow of young fish entering the population. We kept waiting for the kind of strong year class that shows up first as a wave of small fish in the survey, then marches up through the age classes over time. It never really arrived. Instead of a pulse of new cod coming in behind the older fish, we saw a long string of weak cohorts—a dribble where we needed a flood. In the age and length data that fed the models, it showed up as a hollowed-out population: not enough small fish on the way in, not enough big fish making it through to old age.

Climate matters. I have never argued otherwise.

But when a high-profile paper came out tying the failure of Gulf of Maine cod squarely to rapid warming, I watched how the story landed. On the page, it made for striking figures and neat cause-and-effect. In the headlines and policy talking points that followed, the nuance collapsed into something smoother and far more convenient: cod failed to recover because the ocean warmed too fast. It was a clean narrative, the kind that fits easily into a slide deck or a stump speech.

If you’d been living inside the cod assessments, though, that version of the story felt like a carefully selected frame around a much messier picture. Long before the Gulf of Maine crossed into truly uncharted temperature territory, we had been making choices that pushed the stock toward the edge. We kept fishing mortality high even as retrospective patterns piled up, warning that we were overestimating biomass. We gave the benefit of the doubt to optimistic readings of uncertain data and used those readings to defend higher catches. We listened to the reassuring hum of hyperstable catch rates close to port while broader survey trends painted a much leaner landscape offshore. We built rebuilding plans on assumptions about productivity and stock structure that later proved to be wishful at best.

None of that was ordained by climate. These were human decisions, shaped in private briefings and public hearings, during the years when the system still had some slack left in it. Warming didn’t erase that history; it amplified the cost.

That is the risk of letting “climate did it” become the dominant explanation. It isn’t that warming didn’t matter—warming absolutely made recovery harder—but it wasn’t the primary driver. Framed that way, climate becomes a kind of absolution. It pulls our attention away from the levers we actually controlled: how hard we fished, how we handled uncertainty, how we responded when the early warning lights began to flicker. Blaming the ocean’s temperature can feel like an act of realism; it can also function as an alibi.

As the conversation shifted toward warming waters, it was easy for different camps to grab the part of the story that suited them. Some were eager to cast Gulf of Maine cod as primarily a climate casualty and move on, while others treated climate as a distraction from uncomfortable management decisions. But leaving climate out of the discussion didn’t change what was happening in the water, and blaming climate for everything didn’t erase the management record that had brought the stock to the brink.

In the end, cod were being asked to rebuild in a warmer, less forgiving ocean under rebuilding plans that had already overpromised and underprotected. Climate made the hill steeper; we were the ones who spent years kicking rocks loose down the slope.

The author, sampling Acadian redfish aboard the NOAA fisheries research vessel in fall 2008.

The quiet erasure of a stock

Here’s a detail I didn’t fully appreciate back on the Albatross IV in 2008, peering down at too few cod on the sorting table: the Gulf of Maine cod stock I spent those years working on—the single, named population at the center of so many arguments and meetings—no longer exists in the way it did then.

On paper, the Northeast cod complex has since been carved into four different biological stocks. The lines on the map have shifted; the labels have changed. The implications for assessment and management are still being worked out, and in some ways the story is still writing itself. Scientifically, acknowledging multiple stocks is the right move. Cod on different banks and basins don’t all behave the same; they shouldn’t be treated as if they do. The genetics, movements, and spawning behavior all argue for a more nuanced picture.

But what plays well in a journal article can land very differently in a management room. Splitting one troubled stock into several “new” ones brings arguement about boundaries, reference points, baselines, and quotas. It reopens questions just when the answers we already had were screaming for action. Instead of forcing a reckoning with a single, clearly depleted stock, the re-framing added another layer of uncertainty to a system already drowning in it. As a scientific step, it made sense. As a management move, it helped delay the moment when we had to fully admit what we’d done.

However you draw the boundaries now, one truth keeps staring back: even if you can still find small local strongholds where a good day in the right wheelhouse feels like the old stories, Gulf of Maine cod are no longer the dominant, defining stock that once structured the groundfish complex, anchored coastal economies, and stood as the unquestioned emblem of New England’s fisheries.

In my darker moods, I think: they’re no longer worthy of a land mass. Cape Cod still carries its name on every map, a relic of an era when the fish were so abundant that early European explorers thought of the coastline in terms of cod first and everything else second. Today, that name reads less like a description and more like a memorial.

Sunrise on the Gulf of Maine viewed from the back deck of the NOAA fisheries research vessel Albatross IV.

Stepping off the boat

By the time the 2019 groundfish assessments were done, I’d spent the better part of a decade living in the tight space where science, politics, and people’s livelihoods collide: assembling data, wrestling with models that refused to behave, answering questions in public where trust in science was thin and fraying—sometimes as the designated “science voice” peddled to NPR, Discovery Channel crews, or regional papers in search of the sound bite du jour—and watching a stock I was responsible for slide toward the biological equivalent of bankruptcy.

I never stopped believing in the work itself. I trusted the science, respected the skill and hard-won knowledge of working fishermen, and believed in the colleagues in the trenches with me—survey technicians, modelers, analysts, port samplers, observers—doing their best to wrestle meaning from noisy data, not script a convenient answer. What wore me down wasn’t some grand conspiracy; it was seeing how, when uncomfortable results landed, uncertainty could be amplified while what we did know slipped into the background. Senior leadership support often felt thin, and the hardest conversations landed with the people closest to the work. In that environment, science receded into the background instead of guiding decisions.

Eventually, the cost of staying in that world was more than I was willing to pay—especially as the pull to spend my time differently, with a growing family at home, got harder to ignore.

I stepped away from federal stock assessment work—and eventually away from a career and a life I’d spent years building. On paper, it meant leaving a prominent role in one of the Atlantic seaboard’s most closely watched fisheries; to me, it felt less like walking away from a pinnacle than stepping off a listing ship no one could agree how to fix and turning toward work I could live with.

I didn’t leave because I stopped caring about cod. I left because caring about cod—and about the communities that depended on them—made it impossible to keep pretending that if we just tweaked the model one more time, the story would change.

We mismanaged Gulf of Maine cod. We fished too hard, for too long, under rules that weren’t as cautious as we claimed. Climate change made the hill steeper, but it didn’t dig the hole.

I still root for the fish. I still root for the ports and people who rode the cod boom and have been living with the bust. And every time I see the words “Cape Cod” on a map, I’m reminded of the gap between the stories we tell and the systems we actually run.

If cod ever truly get back to “bankers’ hours” again, I hope it’s not because we’ve found new ways to fool ourselves, but because we finally did the hardest thing of all in fisheries:

We believed what the ocean was telling us, even when it meant changing the ending we wanted.

In Cod We Trust poster, featuring artwork by author, and artist, Mike Palmer.