Haddock, Quotas, and the Politics of Science

Colored pencil drawing of a haddock by artist and author, Mike Palmer.

In New England, there’s a word that has fed generations and dodged accountability at the same time.

Scrod.

It’s not a species so much as a promise: something white, mild, and familiar will arrive shortly, and you will not ask too many questions about what it is. You can laugh at the word—and you should—but it also points to something real. A region’s appetite, steady as tide and habit. An economy built around a particular kind of fish: easy to sell, easy to cook, easy to love.

For a long time, cod held that role. Not just on plates, but in identity. Cod could be salted and stacked and shipped through time. It fit the old preservation economy and the old New England story: durable, iconic, inexhaustible—until it wasn’t.

Haddock never had cod’s mythology. It didn’t become the salted emblem. It didn’t travel as well in the old world. Haddock needed modernity—steam power, ice, refrigeration, freezing, the cold chain—before it could become a cornerstone product. But once the technology existed, haddock had something cod couldn’t monopolize forever: a clean, mild fillet that slid perfectly into New England’s scrod-shaped hunger.

And haddock had something else, too—something that doesn’t show up on menus but decides what ends up there.

Recruitment.

Recruitment is the pipeline of young fish that survive long enough to join the population and keep it going. Cod recruitment is variable enough to humble anyone who tries to forecast it. Haddock can be different. Haddock can be episodic—long stretches of small-to-medium year classes punctuated by the occasional boom, the kind of “boomer” cohort that doesn’t just help a stock, but dominates it. When a year class like that comes along, it doesn’t merely add fish. It changes what the fishery feels like. It changes how people plan trips, how plants run schedules, how managers talk in meetings, how confident everyone becomes about the future.

That’s where this story really lives: not in a battle between “science” and “industry,” but in the way a single powerful cohort can make everyone—scientists included—feel like the ocean is behaving predictably.

My haddock story begins in 2008, when I took over the Gulf of Maine haddock assessment. The stock was small and the catches were modest, and the work was—at first—mostly quiet: the updated assessment produced good quotas, and nobody had much reason to argue. The controversy came later, when haddock became limiting in a way that didn’t match what people were seeing on the water.

A haddock caught on the NOAA trawl survey.

The Stock Nobody Took Seriously

Gulf of Maine haddock lived in the background. Not because it didn’t matter—fish were caught, meals were served—but because it didn’t come with the romance. It wasn’t cod: not the myth, not the money, not the history. Haddock was the utilitarian fish, the one that kept plates full without ever becoming a legend.

That quiet status showed up in the science, too. For years the assessment treated haddock in broad strokes—built around big-picture signals that told you whether the stock seemed to be rising or falling, a relative sense of exploitation levels, but not designed to spell out the population’s internal structure. Useful for direction, but not the kind of model that lets you follow the stock like a story.

And stock assessments aren’t only math. They’re credibility. They’re whether people believe the picture you’re drawing is sharp enough to be trusted when it starts to cost someone something. Some stocks get studied like lead actors. Others are handled like background.

Gulf of Maine haddock was background.

Assuming responsibility for the Gulf of Maine haddock assessment, I rebuilt the modeling approach into a framework that tracks the stock by age—how many fish are out there at each year of life, and how each “class” of fish moves through time. That shift changed everything about what you could see. Instead of treating haddock as a single blob that grows and shrinks, you could watch the population’s spine: which generations were holding it up, which ones were missing, and what the fishery was really leaning on.

And once we did that, one thing jumped off the page.

The fish born in 1998—the “1998 year class”—was enormous.

Not “pretty good.” Enormous.

You could see it everywhere: in survey nets, in landings, in the way fishermen talked about haddock as if it had become dependable. That one generation wasn’t just part of the stock—it was driving it. It was the engine behind the stability everyone was feeling.

This is where haddock’s biology becomes both blessing and trap. A boomer year class can make a fishery look healthier than it really is over the long run. It props up biomass. It props up catch rates. It makes the future feel manageable.

But it also concentrates the story in one place. A stock can look “strong” while quietly becoming dependent on a single exceptional cohort. Which means the future eventually narrows to one simple, unstoppable fact:

Those fish will be taken—by nets, by time, or by both.

And then they will be gone.

The Years When Nobody Argued (2008 - 2011)

For several years after the 2008 rebuild, the assessment did what it was supposed to do. The model fit well. The stock story made sense. Projections reflected a population dominated by the 1998 cohort. Those projections drove quota advice. The system functioned.

And because the numbers were favorable enough, the science wasn’t controversial.

This is one of the least talked-about realities of management: most people don’t go looking for a fight with the science when the quota feels generous. When the number isn’t limiting, it’s easy to treat the assessment like a neutral description of reality—an instrument, not an obstacle.

In those years, haddock science didn’t have to defend itself very hard, because it wasn’t standing in anyone’s way. It was largely accepted.

Then the broader world of New England groundfish shifted.

Around 2011, cod began its sharper turn downward. The cod story moved from strained but workable toward worse than we thought. And in a mixed fishery, cod’s decline doesn’t just affect cod. It affects everything.

It becomes gravity.

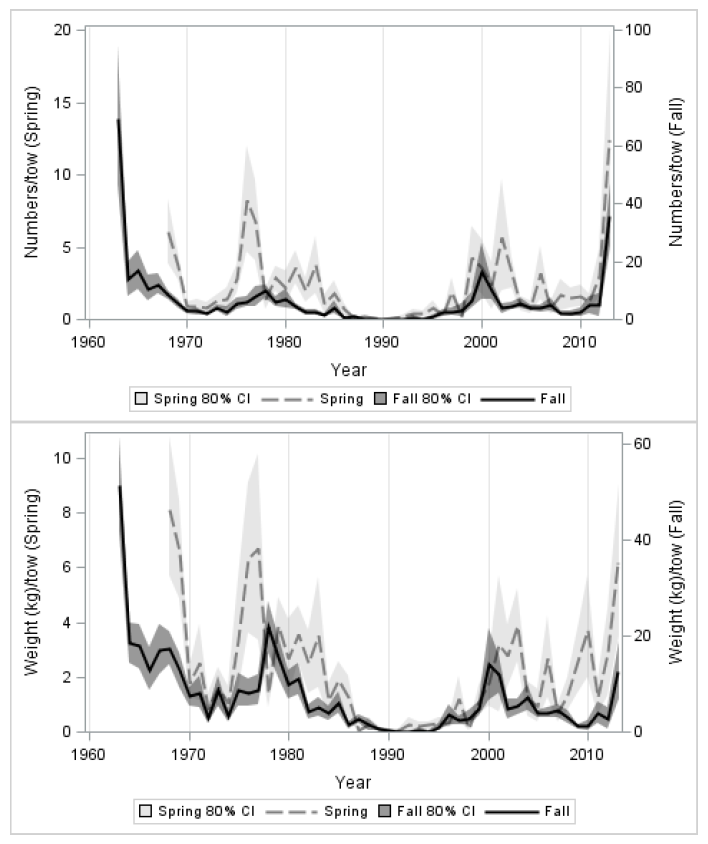

NOAA spring and fall bottom trawl survey abundance (numbers/tow) and biomass (kg/tow) indices for Gulf of Maine haddock from 1963 to 2013. Note that the spring survey did not begin until 1968. Source: NOAA

The Stakes Change: Abundance Becomes the Problem

By 2012, the management system’s mood had changed—not because haddock was scarce, but because the rules around haddock were starting to feel disconnected from what people were seeing in the water. That’s the paradox at the heart of this story: haddock became a limiting stock at the same moment haddock seemed to be everywhere. Scarcity is painful, but it’s legible. Abundance under restriction feels like a category error—like being told you’re rationed on something you can see, day after day, in the net and on the sounder.

When haddock was comfortably non-limiting, the science was background music. The projections were accepted. The debates stayed technical. But once haddock became the bottleneck—the stock that decided whether a trip penciled out—the meaning of the assessment changed overnight. It stopped being, in many people’s minds, a description of the ocean and started feeling like the thing standing between a vessel’s crew and a living. That’s when the attention arrived. That’s when every assumption became a target. The fishery began demanding a story that could reconcile two facts that seemed impossible to hold at the same time: there are a lot of haddock out here—so why are you telling us we can’t catch them?

And then the ocean, with its impeccable timing, made the tension worse by doing what haddock sometimes does. It didn’t just stay abundant. It surged.

Around 2012 and 2013, fishermen began seeing waves of young haddock—enough to feel like a real signal, not a fluke. This is how the ocean announces the future: not with a report, but with juveniles—fish you didn’t expect in those numbers, patterns that repeat just enough to stop being coincidence. The trouble was that those young fish—the early signatures of what would become boomer year classes—weren’t yet fully reflected in the official projections. The quota-setting machinery was still leaning on median recruitment assumptions, because that’s what you do when you’re trying not to overreact to a short-lived blip.

That caution is rational. Haddock is the kind of stock that makes rational caution look foolish—because when a boom arrives, it can tower so far above the median that waiting for certainty feels, on deck, like refusing to see what’s plainly there. The story wasn’t “haddock is declining.” It was simpler, sharper, and more dangerous: the system is behind. And when the system feels behind, people start looking for an explanation that turns delay into error—something technical enough to be taken seriously, and useful enough to move a quota.

That’s when the spillover story arrived.

The Spillover Hypothesis—And the Evidence Problem

Industry pushed hard for a benchmark update to Gulf of Maine haddock. The logic was straightforward: if the population really had shifted—if strong new cohorts were entering the stock—quota advice should catch up.

An industry-driven narrative gained attention: maybe the surge of young haddock in the Gulf of Maine wasn’t truly “Gulf of Maine haddock” at all. Maybe it was spillover from the larger, stronger Georges Bank stock.

It’s easy to see why that story appealed. It comes with a clean visual: fish crossing an invisible boundary. It explains why fishermen are seeing abundance while the projections still look cautious. It translates frustration into something that sounds technical. It takes a messy world and draws arrows on it.

But fisheries management can’t run on arrows. It has to run on evidence.

So the spillover claim went through the process that rarely gets celebrated because it’s not dramatic: the grind of review.

The regional plan development group revisited what had already been done and expanded it—reviewing past studies, re-checking the tracking of year classes through time, looking for patterns in when strong year classes appear together across areas, mapping where the fish were showing up, and running “what if” analyses to see how much the conclusion would change under different assumptions. The idea was taken seriously enough to be tested properly.

The conclusion was blunt:

There was no technical basis for increasing catch limits based on spillover arguments.

The regional scientific oversight committee agreed, and they didn’t just wave it through. They highlighted the risk to the Gulf of Maine haddock resource if catch limits were raised without stronger support—especially given what they described as a lack of compelling evidence from real-world observations.

Tagging data didn’t rescue the story. A fresh look at the cooperative haddock tagging work in the Northeast suggested that most fish stayed where they were: Gulf of Maine haddock had about a 94% chance of remaining in the Gulf of Maine, and Georges Bank haddock about an 86% chance of remaining on Georges Bank. There were important caveats—many tags were released near boundaries and in closed areas, which can make movement look larger than it really is—and reviewers noted that the tagging effort wasn’t designed to reliably estimate year-to-year exchange.

Then came the modeling runs that explicitly allowed fish to mix between the two populations. Those runs landed on the same conclusion, but in a number you can’t talk around: the estimated annual movement from Georges Bank into the Gulf of Maine was low—less than about eight-tenths of one percent.

The federal assessment review process and its independent peer-review panel did not see a basis to treat spillover as the driver of what people were observing. They also did what responsible reviewers do: they acknowledged that pinning down stock structure with higher confidence would take more work. But for management—where you need a lever big enough to move catch advice—the spillover hypothesis didn’t clear the bar.

The arrows didn’t survive contact with the data.

Which meant the system was back to the hard question:

If these fish aren’t immigrants, what are they?

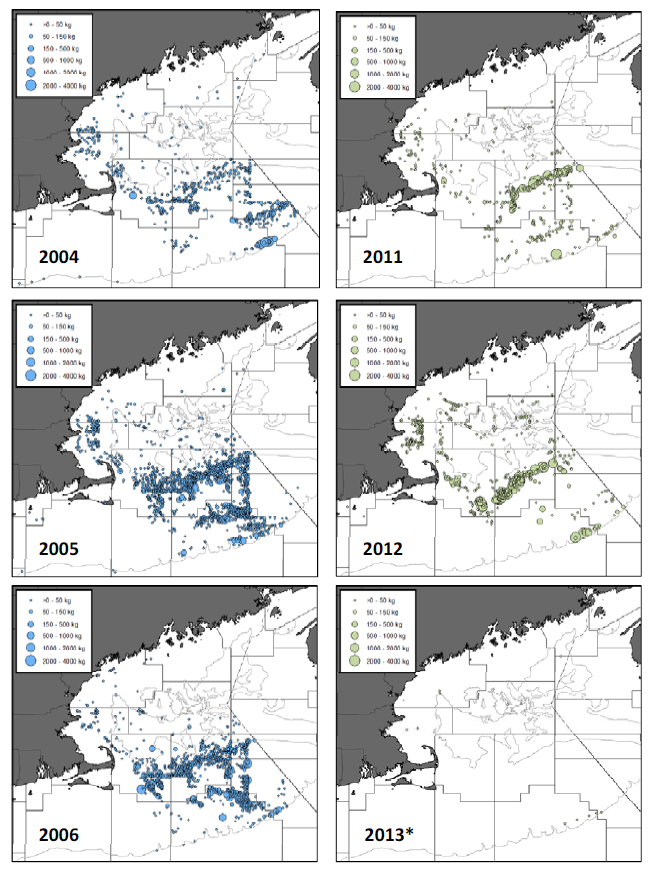

Distribution plots of catches of haddock less than 46 cm as recorded by fishery observers following the spawning of the 2003 and 2010 year classes on Georges Bank. *Note that at the time of the analysis there was limited information available for 2013. Source: NOAA

The Benchmark Update—and the Simple Truth

The answer, when it finally arrived, wasn’t cinematic. It didn’t come with a clever new theory or a dramatic reveal. It came the way most truths arrive in fisheries science: slowly, through accumulation—another season of survey tows, another stack of otoliths read under a microscope, another year of catch records cleaned and reconciled. Less drama, more gravity.

By 2014, enough time had passed—and enough data had piled up—that the haddock story could be told with sharper edges. The stock was taken back through a full benchmark update: the kind of deep, line-by-line review where a model isn’t just presented, but interrogated. Assumptions get challenged. Fits get scrutinized. Alternatives get tested. People who know exactly how uncertain the ocean can be ask, repeatedly, whether the numbers are earning their authority.

In the process, the assessment framework was modernized and strengthened. It moved into a more rigorous age-structured approach that could better integrate what the fishery and the surveys had been hinting at: not just whether haddock were plentiful, but which haddock—how many fish at each age, how cohorts were moving through the population, how the stock’s recent history was actually built.

But the real story of that year wasn’t the upgraded machinery. It wasn’t the technical refinements, the improved fits, the better accounting. Those things mattered, but they weren’t the twist.

The twist was simpler—and far more consequential.

The haddock weren’t visitors.

For a while, people had searched for explanations that could bridge the gap between what the water seemed to be saying and what the projections were slow to confirm. The spillover story had been one of those explanations: tidy, plausible-sounding, and politically useful. But once the new years of information were folded in—once the age data and the survey signals lined up over enough time to stop being ambiguous—a different picture snapped into focus.

The Gulf of Maine had done what it occasionally does when conditions line up: it had produced its own boom.

Two strong year classes—fish born in 2010 and 2012, with another likely following in 2013—were now visible as distinct pulses moving through the age structure. Not as a rumor from the deck. Not as a hopeful interpretation. As something you could point to in the data and watch advance year by year, growing larger, becoming catchable, reshaping the stock from the inside out.

Once those cohorts were properly accounted for, the population estimates changed—because they had to. The science didn’t “decide” to be more optimistic. It didn’t need a new storyline. It simply incorporated what the ocean had already written into the fish.

And when that happened, the advice changed for the only reason advice should ever change:

Because reality had changed.

The quotas rose.

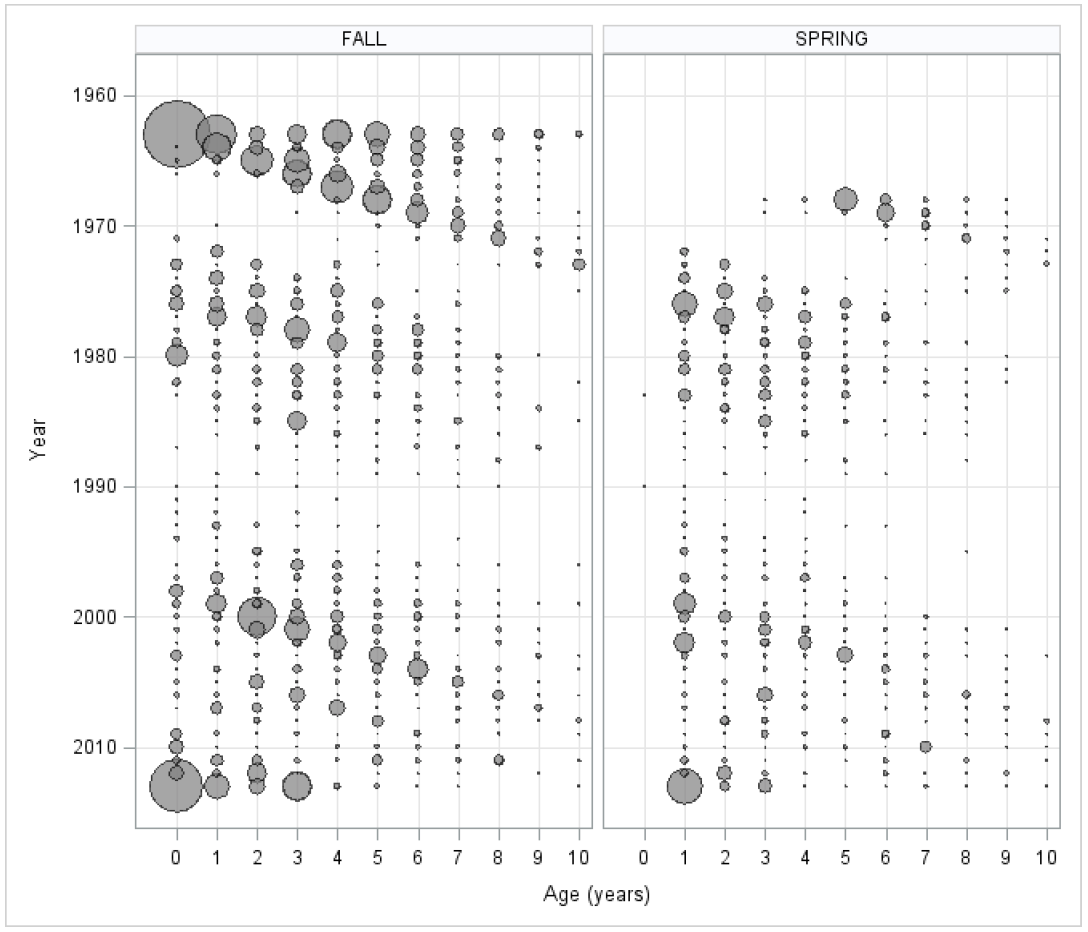

NOAA spring and fall bottom trawl survey Gulf of Maine haddock abundance indices-at-age from 1963 to 2013.

The Part the System Forgets

After the benchmark update, there wasn’t a single moment when everyone stood up and admitted the story had changed. That’s not how it happens. In fisheries, resolution rarely arrives like a verdict. It arrives like paperwork.

A line in the quota table shifts. A fishery notice gets posted. A trip plan looks a little less desperate. The dock talk changes tone. People stop saying “they” with the sharp edge in their voice.

And then, quietly, everyone goes back to work.

The remarkable thing wasn’t that quotas rose—that was biology finally becoming legible in the numbers. The remarkable thing was how quickly the argument drained out of the room once it did. The same inputs that had been treated as suspect when the limit felt irrational—survey tows, age readings, catch histories—were suddenly ordinary again. The same age-structured logic that had been framed as “missing fish” became, overnight, the thing that had gotten it right. The consultant’s arrows lost their urgency. The spillover storyline stopped being a banner and became a footnote.

No retractions. No big public conversion. Just a collective pivot back to normalcy, as if the distrust had been a weather event rather than a position people had taken.

That’s the politics of science in its most revealing form: not a battle over methods, but a battle over pain. When the quota is tight, the assessment becomes a target. When the quota loosens, the assessment becomes background. The uncertainty never leaves—the ocean doesn’t grant that kind of closure—but the outrage does, because outrage is expensive to maintain when the number finally turns in your favor.

The system doesn’t just move on. It forgets.

And that forgetting is not harmless. It’s how the next fight gets preloaded—because if nobody remembers the evidence standards that held when the number hurt, they’ll be tempted to lower those standards the next time the ocean and the quotas diverge again.

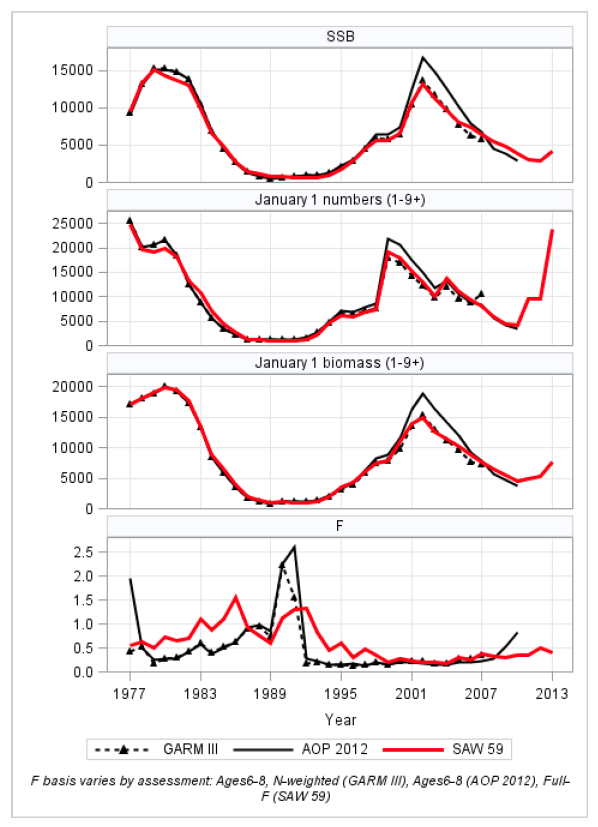

Comparison of estimates of average spawning stock biomass (SSB), January 1 stock numbers, January 1 stock biomass, and fishing mortality (F) from previous age-based Gulf of Maine haddock stock assessments. Source: NOAA

What Haddock Teaches Us

People ask whether fisheries science is political. They ask it when trust is strained.

The honest answer is that science becomes political the moment it matters. When a number determines who fishes and who doesn’t, that number becomes leverage. It becomes the center of gravity in every argument.

But haddock offers a quieter, more unsettling lesson: what we call “trust in science” is often just trust in outcomes.

When the quota is generous, the work is treated as competent. When the quota pinches, the data and the methods become suspect—even when the science is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do: absorb new information, test hypotheses, discard weak stories, and update its view of reality.

In haddock, the system did something that rarely gets acknowledged: it resisted a convenient explanation that couldn’t be supported, and it eventually raised quotas for the right reason—because the Gulf of Maine itself had produced strong new cohorts.

And when that happened, the noise stopped.

That’s the arc, and it’s the point: the method didn’t need to become “better” to become trusted again. Its output just needed to become less painful.

If you want to understand the politics of science in New England fisheries, you don’t start with villain stories. You start with something more human and more consistent:

We welcome science when it gives us room to breathe.

We interrogate it when it tightens our world.

And we often confuse that reaction—our reaction—for a judgment about truth.

In the end, the ocean doesn’t care about our stories. It sends year classes when it sends them. It withholds them when it withholds them. And entire working coastlines end up balanced on those pulses—on whether the Gulf of Maine decides, every so often, to offer a cohort big enough to keep New England eating scrod like nothing fundamental has changed.

Until it doesn’t.