What the River Remembers

The original 1933 Mashpee River biological survey report laid bare.

I rolled into a parking spot behind the Mashpee Archives, a stone’s throw from the Mashpee River. Inside, it wasn’t the dim, dusty room I’d imagined. On a windy-but-warm, sun-struck fall morning, the place felt awake—maps and photographs within arm’s reach, stories stacked in quiet order. I took a seat by the window and opened the hard-bound volume the archivist had set out. The first pages pushed back with the faint resistance of paper rarely turned; between the whisper of the hinge and the smell of old paste, the river began to speak in another era’s hand.

“The water to the north of the peninsula is known as Wakeby [P]ond, while the water to the south of the peninsula, the larger area of water, constitutes Mashpee [R]iver, taking a general course straight south for about four miles, where it empties into Poponesset Bay… thence to the Atlantic Ocean.”

William Dunlap Sargent—young field naturalist, 1930–31—was writing for John Farley, who was busy stitching the Mashpee into a managed trout fishery. For nearly a century, a circle of Boston gentlemen had controlled the middle and lower river through an exclusive club. They kept wardens to turn away poachers, granted entry by favor, and treated the channel like a shop floor: log “hides,” rearing ponds, contrivances stacked against the banks—and, year after year, stockings on the order of 1,000 to 3,000 brook-trout fingerlings per river mile. A hundred years ago, the Mashpee didn’t run wild; it ran under supervision.

A 1930’s log “hide” installed in the middle Mashpee River to provide habitat and refuge for brook trout (Sargent 1933)

“Jim [sic] Farley wanted to stock and raise trout. With his reputation as a hunter and fisherman, Farley chose Tom Mingo as the one to spawn his fish and protect the river. Trout Pond, the small pond just behind Farley’s camp, was the ideal place to propagate the trout and get them to a size where they would be worth catching. Tom and Jim spawned the trout, fed them, and would periodically release some for Jim’s great fishing parties.” (Peters 1987)

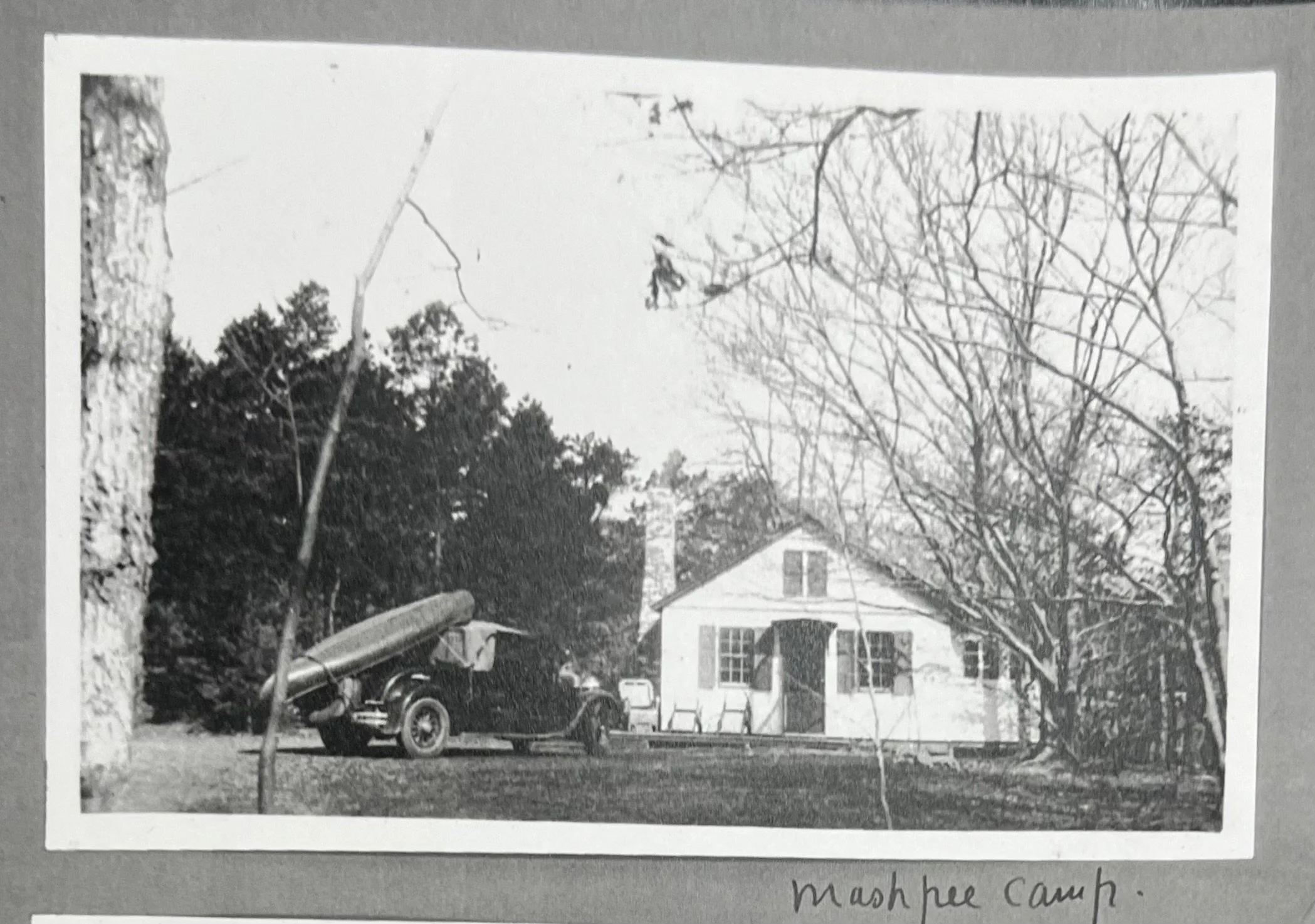

Farley’s mark remains. South of Route 28, on the west bank, a concrete chimney pad still looks over the lower river—the camp pared to its footprint. East of the Pine Tree Corners rotary, he made a hatchery of Trout Pond; spring-fed and cold, it still slips its water into the Mashpee. From that world—owned waters, managed flow—Sargent’s commission took form. His 1933 report, measured and unfussy, endures as a local classic: a slow, careful ledger that still helps today’s naturalists sort signal from noise.

Farley’s camp on the lower Mashpee River (undated, courtesy of Mashpee Archives).

All that endures of Farley’s trout-club era is this hearth, the footprint of a 1900s camp that once supervised a managed fishery along the Mashpee River (background).

Remnants of the spring-fed Trout Pond east of Pine Tree Corners, part of Farley’s 1930s hatchery system that supplied fingerlings to the Mashpee River.

A Tale of Two Rivers

Upstream, the notes turn blunt. Mashpee and Mill ponds ran too warm for trout—known since the 1850s, not long after Mill Pond was impounded. The dam’s fish ladder allowed river herring to climb into Mashpee Pond; the dam lifted temperatures, too, and the adjacent bogs didn’t help. The river’s upper mile threaded between cranberry works—many already sliding toward abandonment—and, like the artificial pond above them, “practically all but one of these was too warm for trout, or trout fingerlings.”

Sargent’s map from his 1933 report indicating key areas along the reach of the Mashpee River. Note that the upper areas of the river are “too warm for trout”.

Then the valley tightened its jaw and changed the story. Topography did the saving. Steep hills pinched the channel into a narrow, fast thread—ill-suited to wholesale bog conversion or millworks. Sargent’s line is spare and exact: the Mashpee’s valley is “longer, narrower, and has more steeply rising sides,” allowed to “maintain itself in a condition which probably closely approximates the original state of all these Cape Cod streams.” Add the quiet subsidy of groundwater: seeps pressing in along the banks, cool as cellars. “Since the volume of water increases considerably from the source to the mouth,” he wrote, the river must be fed by “seepage of underground water… of great value in maintaining the low temperature of the stream throughout the year, especially through the warm summer months.”

A groundwater seep flowing into the lower Mashpee River. These provide a year-round source of cool, oxygen-rich waters to the middle and lower river regions.

In those days the lower reaches were regionally famous: a corridor where native brook trout lived two lives. In fresh water they were the fish everyone knows; as “salters,” they slipped down to Poponesset Bay, fed hard, and returned thick with the bay’s abundance.

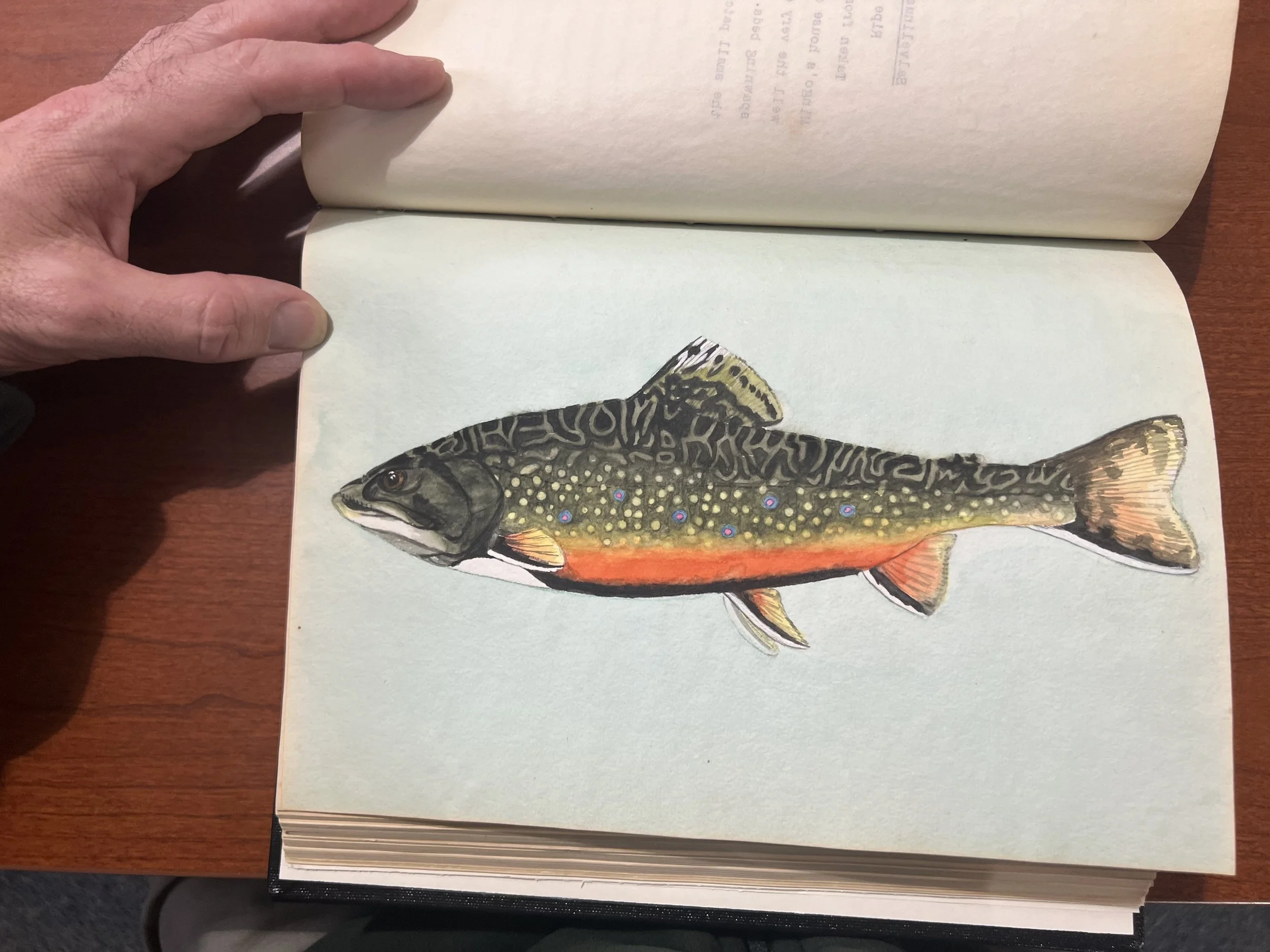

I turned another page and the room changed key. Tucked there—unexpected as a rise in a pool you’d sworn was empty—was a watercolor. Silvered flanks; a long-backed body built for tide: a salter. Not a relic, exactly, but a reference. The kind of image that makes you measure your breath, and then measure the river.

Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill). Female, 15 inches standard length. A sea-run trout, or “salter,” taken in the Mashpee River above Amos’ Landing on May 13, 1931. This fish shows the typical pale coloration of the salters… none of the markings of the ordinary, fresh-water trout are lost, but they are all very much faded.

An original watercolor plate from Sargent’s report - female, 15 inches standard length. A sea-run trout, or “salter,” taken in the Mashpee River above Amos’ Landing on May 13, 1931.

Not rumor. Not a fish tale. A measured fish with a place and a date. It’s also an image anchored in a managed era: with routine stockings of 1–3 thousand fingerlings per mile, it remains uncertain whether trout of this size can persist here without that artificial boost. The notes do accomplish what good notes do, however—fix the scale, fix the location, fix the look. Fifteen inches. Above Amos’ Landing. Mid-May. Muted, colors. Image on one side, evidence on the other.

And suddenly the archive is not a room but a bridge: brush and ledger carrying memory forward, asking, without raising its voice, what the river remembers—and what it might remember again.

Measured in Brushstrokes

I kept reading, but the watercolor wouldn’t let me go. Its image—still, heavy, unavoidable—held fast. Sargent’s prose is spare, almost to a fault, but the painting gives the document a pulse. It insists: this isn’t nostalgia. It’s evidence.

Evidence of a river that sustained more than one way of living. Evidence of fish that learned both routes.

A few more page turns and I found its quiet twin: a smaller trout, darker and mottled, the ordinary freshwater form painted with the same steady hand. Side by side, the pair made the corridor legible at a glance—one marked by the bay’s reach, the other by the uplands’ springs. Between them lay a working hypothesis for the whole system: if you keep the water cold and moving, and you keep the estuary connected, the river will write both chapters.

W.D. Sargent’s watercolor painting of the more common freshwater form of the brook trout. This 8.5” standard length male fish was caught on November 14, 1931 in the middle Mashpee River.

Sargent spelled out the conditions. Clear gravels. Deep bends undercut by roots. Shade that reached the channel when the sun stood high. And, most of all, temperature—the currency that mattered. He noted the upper mile’s troubles, the warmed impoundments, the ditches that hurried heat into the mainstem. He also noted the reprieves: spring seeps, tight valley walls, swift, roughened flow. You could read it as a checklist or a confession. Both would be true.

An approximate 8.5” brook trout caught in the middle Mashpee River on September 27, 2024.

A century later we test the same basics, just with better instruments. We log temperatures every fifteen minutes. We map and measure groundwater flow. We pull herring counts off web dashboards. We argue about culvert openings and floodplain reconnection. We meet landowners in their backyards, asking for a margin of trust along a ditch that used to be a brook. The questions haven’t changed much. Can we cool the hot reaches? Can we sort old ditches from the historic channel and put the river back on its feet? Can we build crossings that pass storms, fish, and future heat? Can we, reach by reach, make the lower river not an exception but a pattern?

Boxplot summary of current (2025) water temperatures on the Mashpee River in the upper river (MR-TEMP-1 through 5), middle (MR-TEMP-6) and lower river (MR-TEMP-7/8).

Is fifteen inches—wild, unstocked—on the table? Maybe. The hinge is the estuary: can it feed fish long and hard enough while enough survive across years? Two levers drive it—estuarine food supply (growth) and multi-year survival (mortality)—and upgrades like nutrient cuts, added structure, and cool-water refuges move both.

The salter watercolor keeps the scale honest: fifteen inches, mid-May, above Amos’ Landing. Those particulars turn a wish into a hypothesis. If that fish needs cold water and an open tide, the work has handles: shade riffles, add wood, replace plug-acting culverts, remove warmwater impoundments. When we can’t drop temperatures, we shorten the distance between cold pockets and spawning gravel so the corridor reads as one system. And the estuary must carry its share: oxygen, clarity, and groceries so every tide adds weight.

There’s a temptation—standing with an old book and a beautiful fish—to mistake art for elegy. Sargent won’t allow it. His pages are stubbornly practical: measurements, margins, sketches of bars and banks, a record of where the river worked and where it didn’t, and what could be possible again. The paintings aren’t trophies; they’re plates—A and B—meant to hold what the notes can’t. That’s their grace, and their demand: not to be admired, but to be tested, until fifteen inches in mid-May above Amos’ Landing is no longer remarkable, just ordinary again.

A small salter (~7”) caught in the lower Quashnet River on April 5, 2025.

From Notes to Work

I think about Farley’s chimney pad on the west bank and what remains of his camp—a footprint of a private idea about how a river should be. Today’s idea is necessarily public. It runs from north of Route 130 to the bay, across boundaries of ownership and memory, across cranberry histories and herring runs and summer crowds. It asks for cooperation more than control, for maintenance more than miracle. And it extends past the river proper to the ponds that feed it, the bogs that hem it, the salt marsh that receives it. The salter painting makes this explicit: you don’t get that fish by fixing a single bend. You get her by fixing the path between rain and tide - from source to sea.

The middle Mashpee River before it leaves its forested valley for the low-lying marsh areas of the lower river.

This is where the title earns its keep. What the river remembers isn’t nostalgia—it’s a working baseline. Sargent’s ledger and those two trout—freshwater and sea-run—are proof that the Mashpee once carried both life histories at the same time. Some days, standing knee-deep below the steep banks where the water still runs cold, it feels close. Other days it feels far. Either way, memory is not enough. It must be paired with work.

So we go back to the list. Cool the warms; reconnect the cut-offs; remove the heat traps; keep the shade. Protect springs the way you would protect a spawning bed. Measure honestly. Keep faith with the fish by keeping faith with the physics. And don’t pretend it stops at the last riffle. The river’s best chance is the bay’s best chance, and the bay’s best chance is the river’s.

The lower Mashpee River, somewhere between the old location of Farley’ s fish camp and Amos’ Landing on a recent fall day.

References

Peters, Russel M. The Wampanoags of Mashpee: An Indian Perspective on American History. Boston. 1987. Nimrod Press.

Sargent, William Dunlap. A Biological Survey of the Mashpee River, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Ithaca, NY. 1933. 243 leaves, illus.