What We Risk by Not Looking

A Quashnet River brook trout in spawning condition.

Last fall, in the thin-leaved season when the Upper Quashnet becomes easier to read, I watched trout spawn in flashes—rush, gravel, retreat—like the river was breathing in quick, urgent pulses. A bright patch of newly turned stone appeared and disappeared beneath them, small enough to miss if you were in a hurry, important enough to carry the future of the river. It wasn’t a spectacle. It was proof. And it made me think about how easily places like this are changed—not with a single blow, but with the slow confidence that comes from not paying attention.

They held in shadow for long moments, and then—suddenly—shot into the open as if on a signal: tails beating, bodies twisting, gravel lifting, the riverbed briefly alive. Just as quickly, they slipped back to cover. It came in waves: a short spawning frenzy, then flight, then another rush. Even here, even now, the work of making the next generation is risky. It depends on cold water arriving on time. It depends on oxygen moving through clean gravel. It depends on fine sediment not filling the spaces where eggs need to breathe. It depends on an integrity that’s hard to describe until you see it—and hard to recover once it frays.

I stayed longer than I meant to, not because it was dramatic, but because it was precise. Brook trout don’t negotiate at spawning time. They either find what they need or they don’t. A small patch of gravel can end up doing outsized work for an entire river.

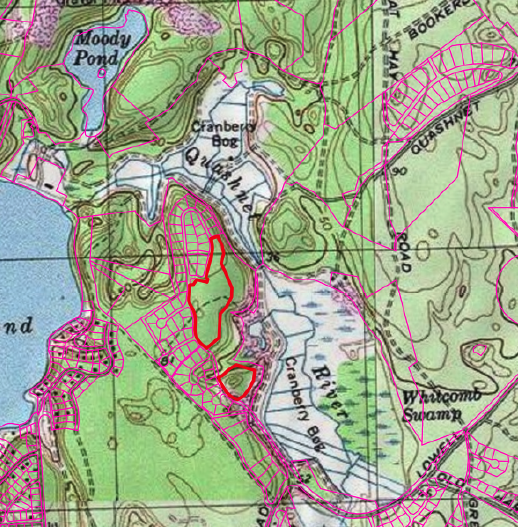

Location of the proposed development (red), due west of the upper Quashnet River.

Not far from that place, change is expected to arrive in a more recognizable form. A residential project—The Reserve at Quashnet Valley Country Club—is moving forward directly adjacent to this headwater landscape. The important nuance, too often missed in the way we talk about growth, is that the project is grandfathered in. The question isn’t simply whether something happens. The question is how it happens, and whether choices made right at the river’s edge are careful enough to honor what the river is already demonstrating.

In headwaters, “how” is not a philosophical word. It’s a design word, a maintenance word, a groundwater word. It’s the difference between rainfall that filters slowly into sand and returns later as steady, cold baseflow, and rainfall that is hurried off hard surfaces, warmed and carrying whatever it picked up, arriving in the channel like an interruption. It’s the difference between gravel that stays clean enough to breathe and gravel that slowly silts in, season after season, until the redd disappears without ceremony.

And “not looking” isn’t only a water story. Rivers like this have been travel routes and home places for a very long time, and the Upper Quashnet sits within a cultural landscape that matters deeply to the Mashpee Wampanoag. It’s entirely possible that what looks like ordinary ground could contain clues to earlier use—sometimes subtle, sometimes significant. Building here is not an indictment; it’s the next layer in a long pattern of people living close to water. But modern projects can do something earlier generations often couldn’t: pause long enough to look. Thoughtful archaeological investigation and Tribal engagement help ensure we don’t confuse “unseen” with “unimportant,” and they give the community a chance to make informed choices about how to treat what’s discovered—whether that means avoidance, documentation, or respectful management.

This moment in the headwaters also sits inside a larger story that is still being written. The Town of Mashpee has started the design work to restore a substantial stretch of the Upper Quashnet—work aimed at rebuilding function where it has been diminished and protecting what still remains. And now APCC has secured multi-million-dollar funding to carry that effort forward through final design and into construction. In other words, this isn’t a watershed where people are shrugging at the future. It’s a watershed where intent is being translated into plans, and plans are being positioned to become work on the ground.

Downstream, the Quashnet carries an even longer memory of care. For decades, volunteers and partners—many through Cape Cod Trout Unlimited—have been doing the slow, unglamorous work of restoring the lower river. It’s the kind of effort that rarely makes noise, but changes what a place can be, and keeps changing it long after attention moves on.

That downstream recovery is part of what is at stake here, because watersheds don’t respect the neat boundaries we draw on plans. A headwater reach can be doing its job beautifully and still be compromised by small, repeated inputs right next to it. Fine sediment accumulates quietly. Warm storm pulses arrive in summer. Nutrients move through groundwater and, over time, feed the wrong kind of productivity. And in Waquoit Bay—already living with the long consequences of what arrives from the land—the “a little more” doesn’t vanish. It collects. It changes the baseline. It becomes the new normal.

The lower Quashnet River, running through the heart of the Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge.

This is where nearby examples matter, not as scare tactics, but as reminders of how change often arrives. The Santuit River is still spoken about with a kind of ache: a place that once held sea-run brook trout in a landscape that doesn’t offer many such miracles. Its decline wasn’t one dramatic moment. It was a quiet shift in conditions over time, and then the slow realization that what people loved had become harder to find. When headwaters tip, they rarely do it loudly.

It’s tempting to focus on water quantity—whether new homes “draw down” the system. Here, the picture is more nuanced. The homes are expected to be on town water, while irrigation would come from wells. With thoughtful stormwater infiltration, the site can be designed to keep rainfall on the land and moving into the ground in a way that keeps net recharge stable, and in some cases improves it compared to older runoff patterns. Quantity may not be the headline risk if recharge is treated as a design priority rather than an afterthought.

But the river cares just as much about what the water carries, and how it arrives.

Wastewater is the long game. It shapes the nutrient story slowly, persistently, in ways that are easy to ignore year to year and impossible to ignore over decades. If there is a realistic opportunity to connect into existing treatment infrastructure, it deserves a straightforward look grounded in feasibility and long-term performance. If a cluster system is the path, then the real question is whether it will be treated like true infrastructure: professionally operated, transparently monitored, and built with accountability that lasts long after construction becomes memory.

Stormwater is the short game. It arrives fast—hot in summer, forceful in heavy rains. Done well, it can be captured, treated, cooled, and infiltrated in ways that protect the riverbed from sediment, protect coldwater margins from thermal spikes, and prevent a stable system from becoming a flashy one. Done poorly, it can deliver exactly the ingredients that smother spawning gravel and narrow the conditions that made that bright patch of gravel possible in the first place.

There is one more truth worth saying plainly: doing nothing is not neutral. Defaulting to minimum solutions doesn’t preserve a river; it merely postpones consequences. The cost of inattention is predictable. Nutrient enrichment grows. Algae becomes more common. Oxygen stress deepens. Cold refuges shrink. And one day, without a single moment you can point to, the redd stops appearing.

None of this requires a posture. It doesn’t require being for or against development. It requires something quieter and more demanding: the willingness to stay engaged long enough that plans become outcomes, and that “maintenance” remains a commitment instead of a line in a document.

That fall morning is the image I keep returning to: trout launching out of shadow, boiling over bright gravel, then slipping back into cover. A life-and-death rhythm in a place small enough to miss if you’re in a hurry. The river wasn’t making an argument. It was demonstrating function.

If something is going to be built beside that kind of function, the best outcome isn’t silence and it isn’t outrage. It’s a community that stays curious and steady, and insists—politely, persistently—that the “how” be worthy of the place. So that design work becomes construction, construction becomes resilience, and the stories held in water and soil are carried forward with eyes open.

A culvert at a dirt-road crossing of the upper Quashnet River, located near the proposed development area.